Numbers, birth date and months in Lithuanian

Ah numbers, one of the most important things you learn as an infant. This, after letters, words, colors, shapes, animals. As an adult learner though, it probably just has to be one of the most essential things to know to function in society. You need numbers to count, to purchase items, to give out your phone number, your age, your street address and the list goes on and on. In this module, we will talk about numbers, how to ask for and indicate age and months in Lithuanian.

Are you in for a bumpy ride? You may think you got the hang of speaking Lithuanian but wait ‘till you get to the end of this module. It’s about to get more exciting!

Numbers, just like words, are often written in their dictionary, nominative form. Along with these, we will also learn how to use them to talk about your age and your birthdate. And as you will see, this entails mobilizing the other cases: accusative, genitive and instrumental. While these three cases do serve their purpose to modify certain linguistic elements, in Lithuanian though, there seems to be no consistent logic - i.e., it just is. I was (still am, to be completely honest) perplexed as how this works. It seems that one has to think about a great deal of rules just to indicate such a short and simple information. My advice? Just take it as it is, use them accordingly and do not give it too much thought. You’ll get the hang of it eventually.

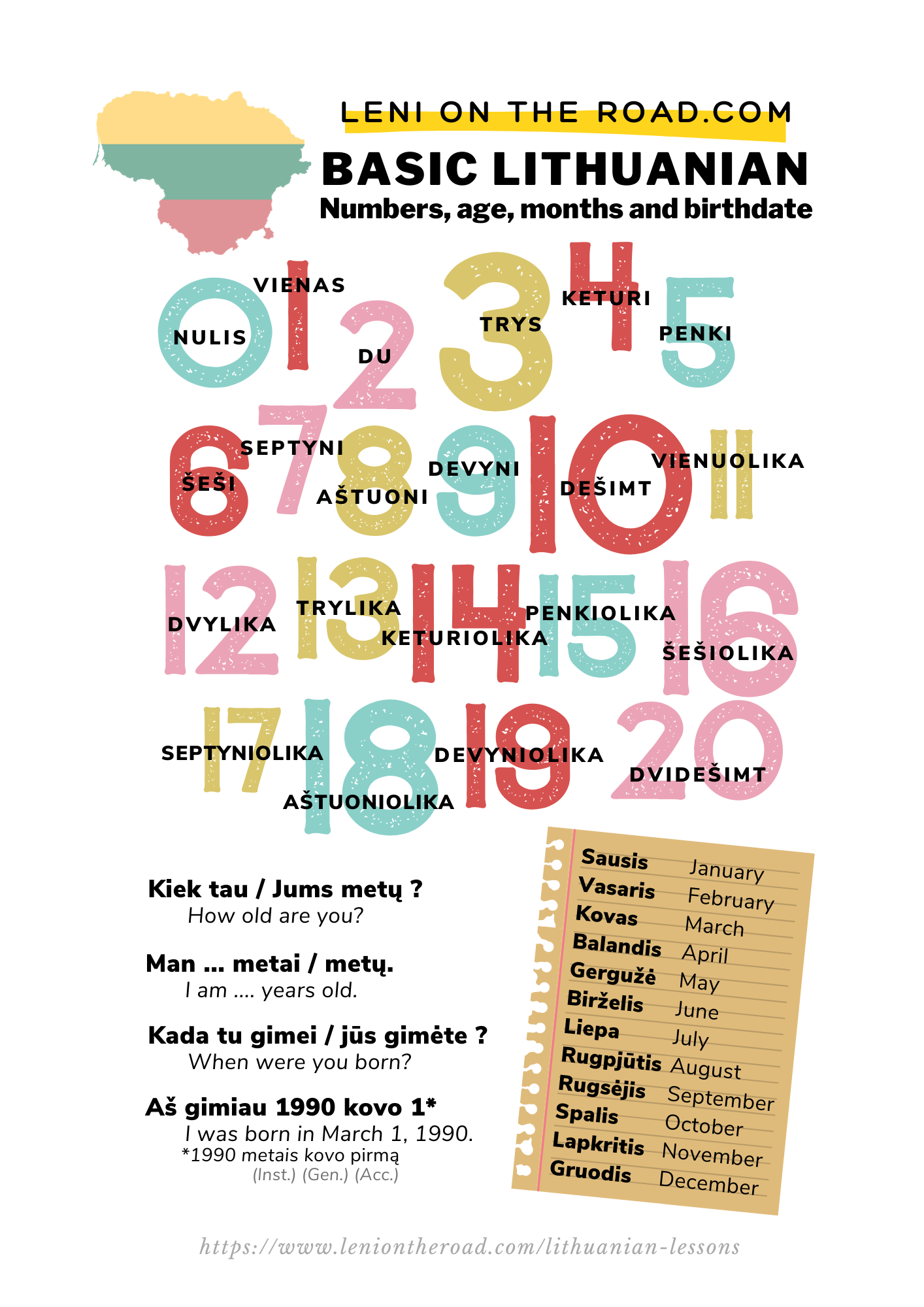

Don’t back out just yet! I tried to make it as simple as I can, starting with laying out the vocabulary for Lithuanian cardinal numbers (which also changes according to gender, the following are masculine, by default):

0 - nulis

1 - vienas

2 - du / dvi

3 - trys

4 - keturi

5 - penki

6 - šeši

7 - septyni

8 - aštuoni

9 - devyni

10 - dešimt

The hundreds are compound numerals. Take note that from 200 and up, šimtas take in a plural form šimtai.

100 - šimtas

200 - du šimtai…

101 - šimtas vienas

555 - penkta šimtai penkiasdešimt penki…

This goes for the thousands as well. Here’s when it starts to get tricky, though. Besides the singular form as used in 1000 (tūkstantis), numbers from 2 000 - 9 000 takes a plural ending (tūkstančiai), and numbers that end in 0 from 10 000 takes a different ending (tūkstančių).

1 000 – tūkstantis

2 000 – du tūkstančiai

10 000 – dešimt tūkstančių

11 000 – vienuolika tūkstančių

Once you learn these first 11 numbers by heart, the rest will go on fairly simply. Take the stem of the number and add + -(io)lika.

11 - vienuolika

12 - dvylika

13 - trylika

14 - keturiolika

15 - penkiolika

16 - šešiolika

17 - septyniolika

18 - aštuoniolika

19 - devyniolika

The tens are formed by adding the ending -dešimt (ten). From here on, just like in English, add the tens + the first 9 numbers:

20 - dvidešimt

21 - dvidešimt vienas

22 - dvidešimt du

30 - trisdešimt

33 - trisdešimt trys

40 - keturiasdešimt

44 - keturiasdešimt keturi

50 - penkiasdešimt

55 - penkiasdešimt penki

60 - šešiasdešimt

66 - šešiasdešimt šeši

70 - septyniasdešimt

77 - septyniasdešimt septyni

80 - aštuoniasdešimt

88 - aštuoniasdešimt aštuoni

90 - devyniasdešimt

99 - devyniasdešimt devyni

Are you still with me?

If you recall from the previous module on the days of the week, Lithuanian days are labeled in order. It makes use of the Lithuanian ordinal number. In English, this is where we make use of the words first, second, third, fourth, etc. Except for the first three digits which are uniquely their own, we simply add -th to the cardinal number to indicate ordinal numbers. The same logic follows in Lithuanian numbers where you simply add -as.

First - pirmas

Second - antras

Third - trečias

Fourth - ketvirtas

Fifth - penktas

SIxth - šeštas

Seventh - septintas

Eighth - aštuntas

Ninth - devintas

Tenth - dešimtas, etc.

Talk about your age

Kiek tau / Jums metų ?

- Man 29 metai. Man 18 metų. Man 40 metų.

Translation:

How old are you?

- I am 29 / 18 / 40 years old.

The question Kiek tau / Jums metų ? literally sounds like “How much age is on you?” or something to that effect. However, it is aptly translated as “how old are you?” In English.

In this exchange, we introduced a new interrogative word: kiek ? (how much).

Metai and metų are two different forms of the word “year” as we will see later on. Stick with me.

At this point, you probably know the difference between tau and Jums. Kiek tau metų ? is the informal way of asking how old someone is while replacing tau with Jums makes it formal: Kiek Jums metų ? Simply answer Man ... metai / metų, indicating your age in the space between man and metai / metų. Notice that you either use metai or metų. As explained above, numbers, (including 1 this time around), should be modified using the plural metai. On the other hand, numbers 11-19 and numbers ending with 0 should be modified using metų.

Still doing okay? We’re nearly done but the brutal truth is it’s not getting any simpler.

Talk about your birth date

Kada tu gimei / jūs gimėte ?

- Aš gimiau 1990 m. kovo 1 d*

Translation:

When were you born?

- I was born on March 1, 1990.

To talk about your birthday, you would need an additional set of vocabulary: the Lithuanian months of the year, along with some trivia about the names attributed to these months:

Sausis - January

Meaning “dry”. January is in the middle of winter in the northern hemisphere where the snow is very cold and dry.Vasaris - February

From the word vasara, meaning summer. This is misleading because February is still winter time when people start to dream about warmer days ahead.Kovas - March

Comes from the bird rook when these birds come back in Lithuania.Balandis - April

Or “pigeon” in Lithuanian when people are reminded of this type of bird due to the birds chirping and the color of the surroundings as winter transitions to spring.Gergužė - May

Or the Lithuanian “cuckoo" when they start to be heard.Birželis - June

From biržis, a mark where grain should be planted. June is the month where people start to plant.Liepa - July

Meaning “Linden tree” when it starts to bloom.Rugpjūtis - August

Which is “ryes” in Lithuanian when the ryes from the previous year are being harvestedRugsėjis - September

Also related to ryes, literally means “sowing rye” where the ryes for the next harvest are being planted.Spalis - October

Meaning “fragments of the husk of flax” when husks of flax are beatenLapkritis - November

That time of the year where leaves start to fall as autumn ends and winter approachesGruodis - December

From “gruodas” meaning lumpy frozen land when cold winter days are about to start

Date format

Dates in Lithuanian are given out in a different format: the year comes first (m for metai, year), followed by the month, and finally, the day (d for diena, day). The logic is to start first with the most general information down to the most specific.

Notice that March in the sample dialogue is identified as kovo as opposed to what is given in the vocabulary set which is kovas. It’s the same word but as it is used in the date and sample dialogue, kovas was used in its genitive form: kovas (nom.) to kovo (gen.). This being said, when indicating your birth month, the nominative case of the months should be transformed to the genitive case as follows:

Sausio (gen.) - Sausis (nom.) - January

Vasario - Vasaris - February

Kovo - Kovas - March

Balandžio - Balandis - April

Gegužės - Gergužė - May

Birželio - Birželis - June

Liepos - Liepa - July

Rugpjūčio - Rugpjūtis - August

Rugsėjo - Rugsėjis - September

Spalio - Spalis - October

Lapkričio - Lapkritis - November

Gruodžio - Gruodis - December

Getting the hang of it yet? We’re not quite done yet.

How do you pronounce the day? In the same dialogue, the birth date is March 1, 1990. In English, you simply read it as it is : march one nineteen ninety. We already saw how some transformation from nominative to genitive is necessary for Lithuanian months, surely the numbers are read as it is? Not quite. 1990 m. kovo 1 d is read as : tūkstantis devyni šimtai devyniasdešimt metais kovo pirmą. In addition to reading the days using the ordinal numbers (first, second, etc.), observe how there’s a nosinė (review: Lithuanian alphabet) on the final letter “a” in primą. This indicates the accusative case. Fret not, it doesn’t get anymore complicated as the pronunciation will relatively remain the same.

Gimti, gimsta, gimė (to be born) and the past tense

When talking about your birthday, we used a newly introduced interrogative word kada (when) and the regular verb gimti (to be born) in the past tense. The conjugation is therefore different from that of the present tense which we have been seeing in the past modules:

Aš gimiau

Tu gimei

Jis/ji gimė

Mes gimėme

Jus gimėte

Jie/jos gimė

✏️ Challenging isn’t it? That’s a good sign of progress. Comment below with your age and birthdate (you can omit the year) for privacy concerns.