Visiting the Cité internationale de la langue française

Courtyard entrance to the Cité, with the chairs spelling out “I love” in Arabic نا احب

We drove to Villers-Cotterêts on an unremarkable weekday morning during our staycation in the Oise. The road was calm, the weather indecisive - chilly but overall a good day for a visit about language: slow, attentive, unforced. This town also happens to be the birthplace of Alexandre Dumas, author of my favorite French novel, The Count of Monte Cristo. That coincidence landed more personally than I expected. Villers-Cotterêts was where French became official and where one of its great storytellers began.

The destination was the Cité internationale de la langue française, housed in the Château de Villers-Cotterêts. After years of restoration, the site has been reborn as a place dedicated not just to French as a system, but to French (language) as a lived experience. Spoken, argued over, written, borrowed, reappropriated, reclaimed, or reshaped.

If you’re planning to visit:

€9 for the permanent collection.

€12 for permanent and temporary exhibitions combined.

Closed on Mondays, more practical information here

Accessible from Paris by TER (regional train) via Gare du Nord

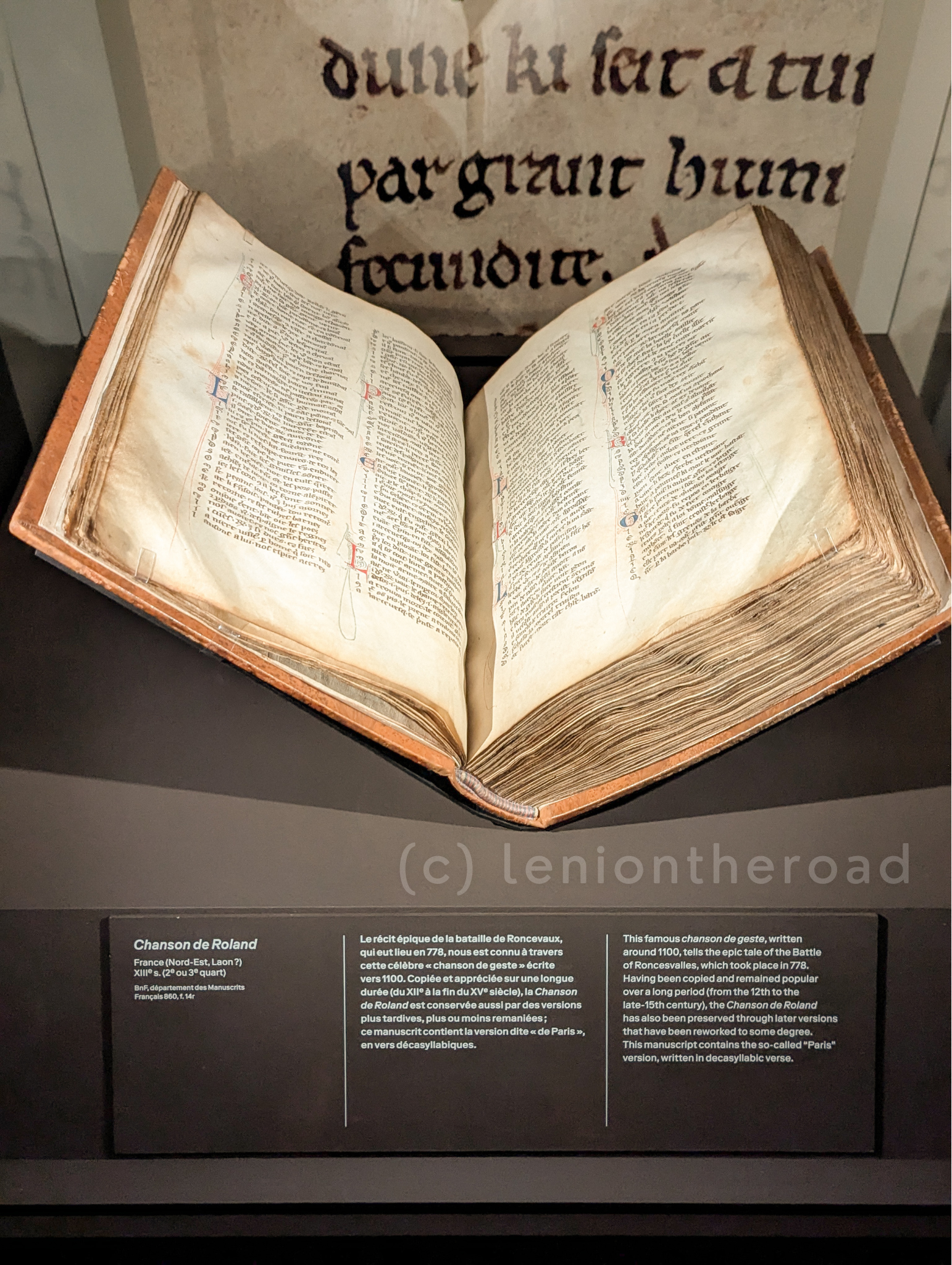

Chanson de Roland, written circa 1100

When we visited, the temporary exhibition came from the Bibliothèque nationale de France: Trésors et secrets d’écriture. Manuscrits de la Bibliothèque nationale de France, du Moyen Âge à nos jours. Glass cases held fragile manuscripts. I found myself gushing over the original text of La Chanson de Roland — works I used to read in fragments while learning French at university. I also nerded over the drafts of great minds like Descartes, Diderot, Champollion, Levi-Strauss, Proust, Camus, Hugo, de Beauvoir, but also Weil, to name a few. I never imagined I would one day stand in front of them, that I would actually lay my eyes on the very pages themselves. I leaned in, tempted to decipher Latin, Old French, and French I could actually understand - beautifully scripted on parchment in the dimly lit room.

Their penmanship was impeccable. What patience it must have taken to contain fast-flowing thoughts in such disciplined lines. It reminded me of the hours I once spent writing down my own thoughts in a journal (not with any great talent, but) with the same quiet devotion to words and the simple pleasure of good handwriting.

Inside the main galleries and permanent connection, modern technology does most of the talking. Maps animate the migration of words. The Cité presents French as a living, moving body.

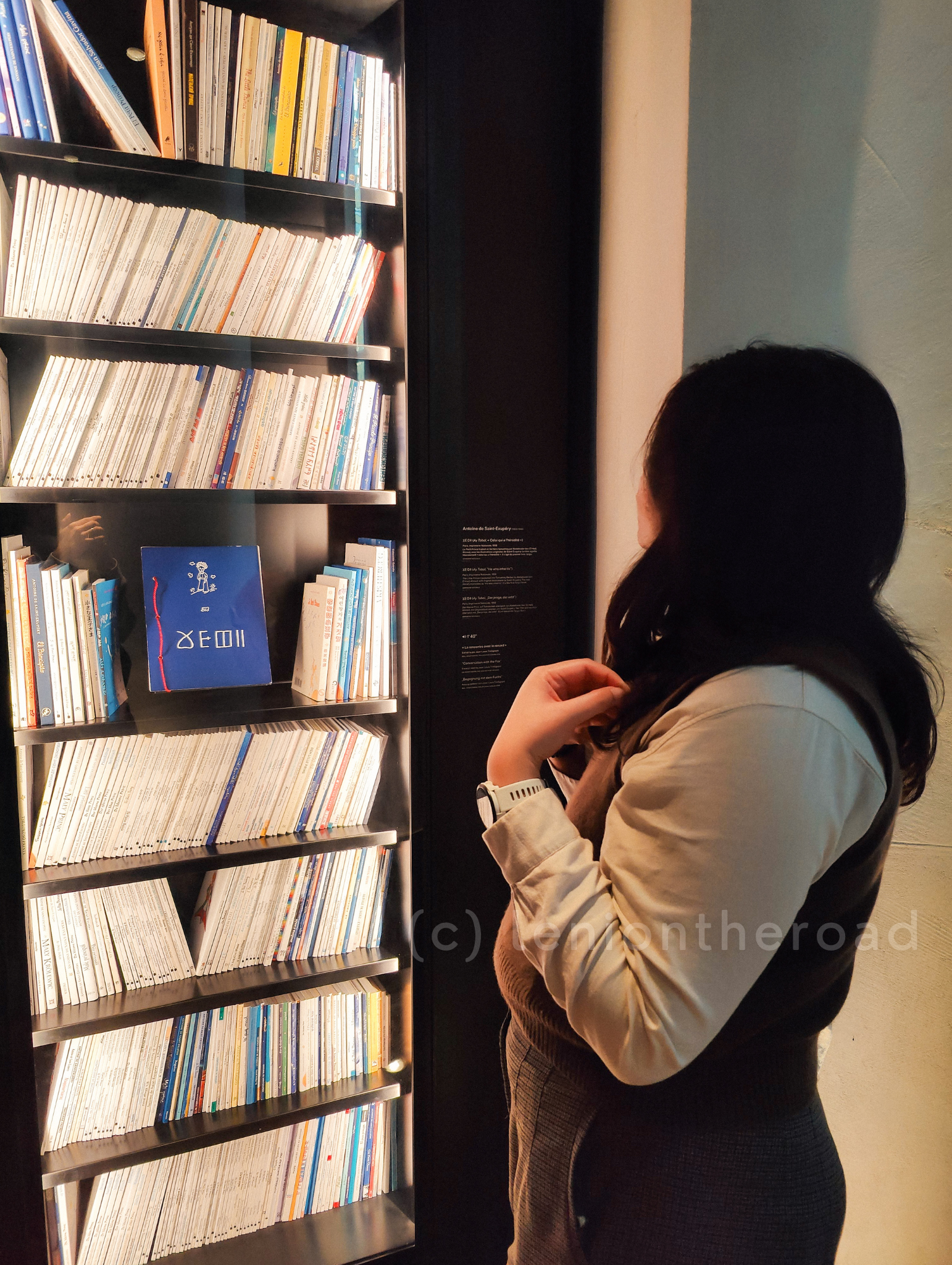

My favorite corner was an alcove displaying translations of Le Petit Prince from around the world. Dozens of familiar covers, all slightly altered by their adopted tongues. I’ve started my own modest collection of these editions from my travels, and standing there felt like seeing a private habit unexpectedly validated.

The alcove with versions of Le Petit Prince

Another room reconstructed French across the centuries; how it sounded before it we speak it today, how spelling resisted obedience, how grammar was once more suggestion than law. Everything invited touch, listening, trial. It was definitely more than an exhibition; it was more of an experience, an interaction, a conversation.

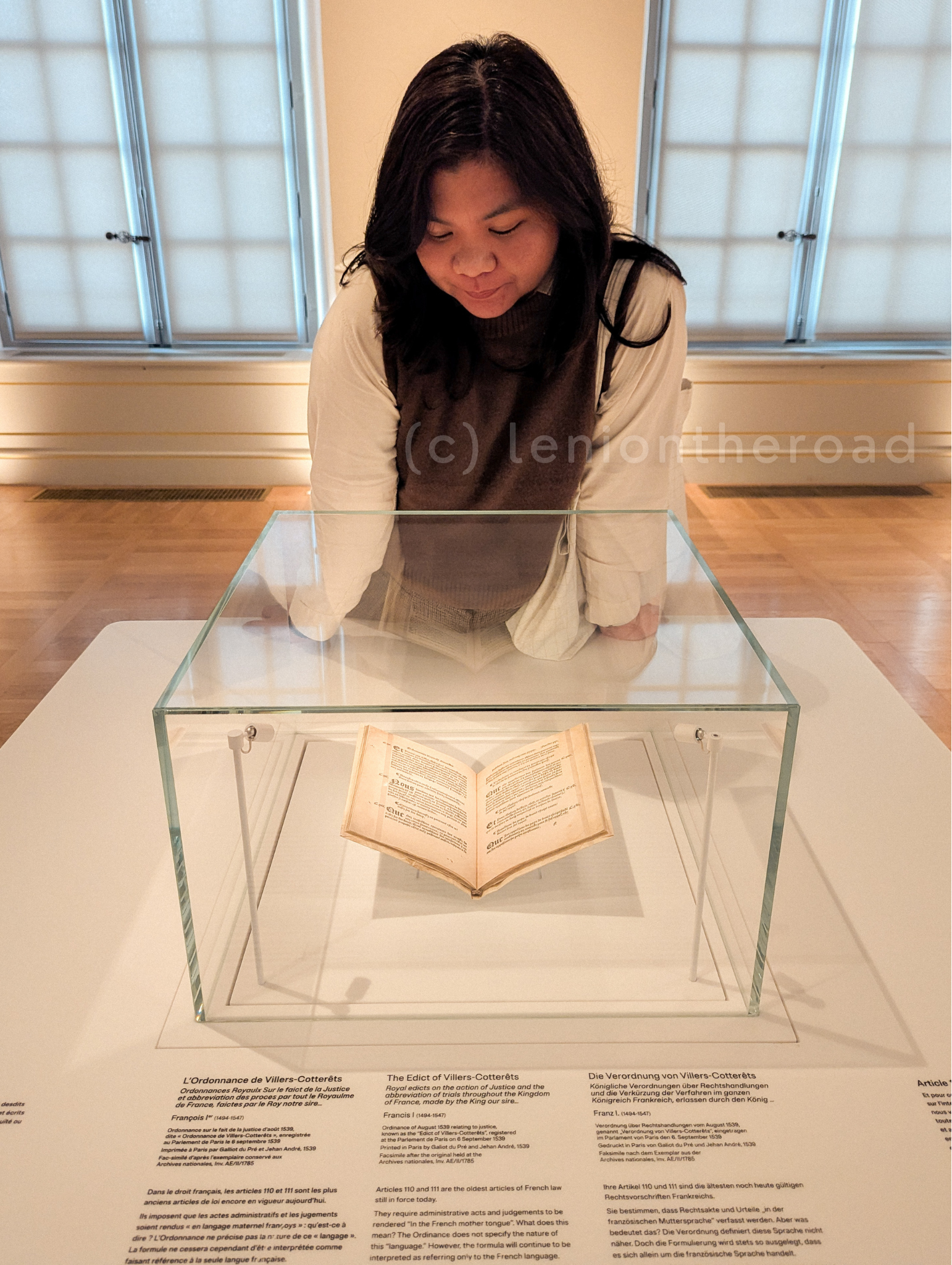

What struck me most was the last few rooms before the exit. It was solemn, quieter. Behind protective glass lay the original copy of the Ordonnance de Villers-Cotterêts, articles 10 and 11. These are the lines that made French the official language of legal and administrative acts in France. In school, this decree is usually reduced to a date and a consequence. In person, it feels heavier: the moment language becomes statecraft.

Walking through the galleries felt oddly like visiting different versions of myself: the one who once struggle with learning the language, eventually being mesmerised by it, or the one who didn’t quite become what she imagined. So many emotions in such a short span of time. I feel like I lost myself there, like I was a lotus-eater, and not at the same time, such a complex feeling all at once, none of these words I attempt to write down could come close to the exact feeling. How frustrating is that? A language enthusiast, unable to capture their thoughts with the one thing they know best. I digress. Let me continue to attempt.

I don’t identify as an intellectual. But I enjoy being around them. I like spaces where thinking is allowed to be slow and detailed.

Before visiting, over lunch at a nearby restaurant, B asked if I was excited to finally visit. I told him I felt both happy and sad. Happy because the visit felt like the fulfillment of a small, forgotten promise. Sad because none (?) of the people I once studied (or worked) with in French would share this (level of) enthusiasm now. We have all gone our separate ways. I did go out of trajectory, too. I no longer do what I once set out to do, and that’s not a tragedy. But I miss teaching. I miss expermenting different techniques for students to learn, remember, use, and acquire the language. I miss watching students discover that a new language doesn’t replace the old ones; it adds rooms to the house.

I still speak French every day. To some extent, while fluent, but in a less eloquent way. Also, I no longer pass it on. I use French in a very different context than I used to.

Going through the activities, enjoying them with B, we both thought: you don’t observe a language at a distance; you step into it, and you live it. If some people have Disneyland, this was mine, Villers-Cotterêts, an unpretentious place tucked in the Retz forest.

The visit also raised a larger question: what is the place of French today? President Macron declares that the most French speakers are not in Paris, nor in France, but in Kinshasa, capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Read more: French around the world). Proof that French no longer just belongs to the French [in France], nor are they the sole authority (search for the concept of linguistic plurality, to know more).

B also remarked how fascinating it was that a whole “cité” could be built around a language. He asked what I thought. I said I liked how historical it was, but also how political. Language touches everything: literature, law, migration, class, belonging, but most especially, identity.

Oldest French legislation still used partly by French courts.

At the inauguration of the site in 2023, Emmanuel Macron insisted that this is not a museum but a cité, because a language is not an object but it is lived by its people:

“la Cité "n'est pas un musée", souligne son directeur Paul Rondin. "On n'est pas ici pour conserver la langue française mais pour la faire vivre, révéler sa diversité extraordinaire. (France Culture, 2023)"

There are debates about the raison d’être of this place: preservation versus control, celebration versus nostalgia, language norms vs actual use. But to me, it felt like something more of a celebration of ideas and of people, of unity. We often argue that language divides, that it colonizes, that it excludes. All of that can be true. But I have always experienced it as something that connects, bridges, and unites. It lets strangers share coffee. It lets the past speak to the present.

The visit also stirred an older, quieter dream in me: to one day see (or help build) a similar initiative for the languages of the Philippines. A place where Tagalog, Cebuano, Ilocano, Waray, and so many others could be heard, traced, and honored not as relics but as living forces. I have long carried another linguistic pilgrimage on my list as well: the Museu da Língua Portuguesa in São Paulo.

I could keep going. But maybe this is the part where I stop and leave you with an invitation to go see it for yourself, if the opportunity permits. And if you can’t, get into a conversation with me, it’s gonna be a passionate one, for sure! But if you do get to visit, please tell me about it—over coffee, perhaps. Or better yet, let’s go again. Together.